Table of Contents

Genocide is the gravest crime recognised under international law. It is defined in the 1948 Genocide Convention as the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group. The Convention was created after the Holocaust and was meant to serve as a legal safeguard for humanity.

Yet the global legal system has repeatedly failed to prevent or halt genocide – just take the issue of Gaza, for example – something that captures the ultimate flaw of our society. Politics, jurisdictional limits, and slow legal processes often leave vulnerable populations exposed. By examining several major atrocities, we can see both the legal obligations that exist and the structural weaknesses that allow such crimes to occur.

How International Law Addresses Genocide

Under the Genocide Convention, states have two major obligations:

- To prevent genocide

- To punish genocide

To prove genocide, courts must establish:

- a protected group

- prohibited acts

- specific intent to destroy the group

This requirement of intent is the central legal challenge. Most perpetrators avoid explicit statements of genocidal intent, which leaves courts struggling to meet the legal threshold until long after mass violence begins.

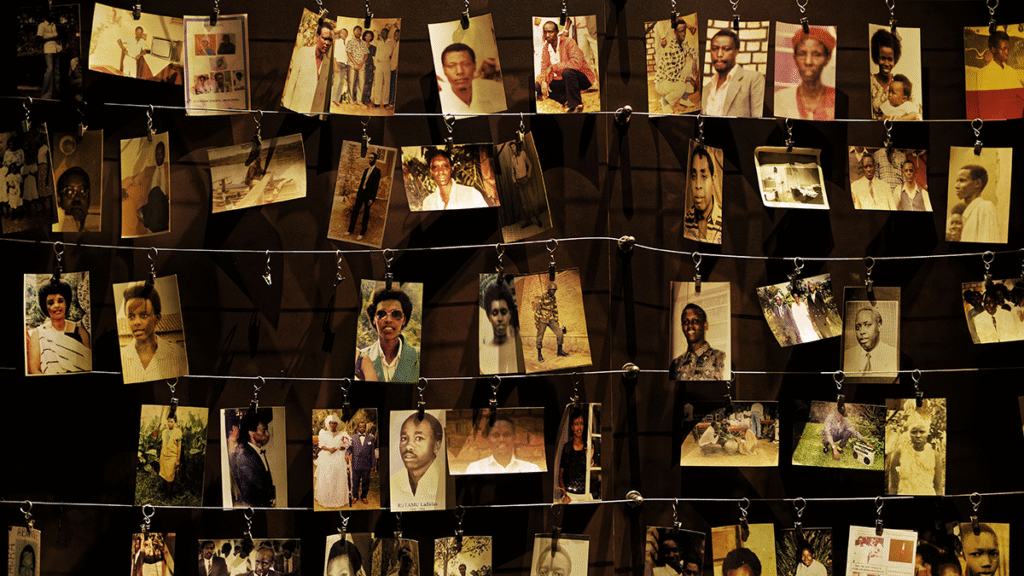

Rwanda

Background

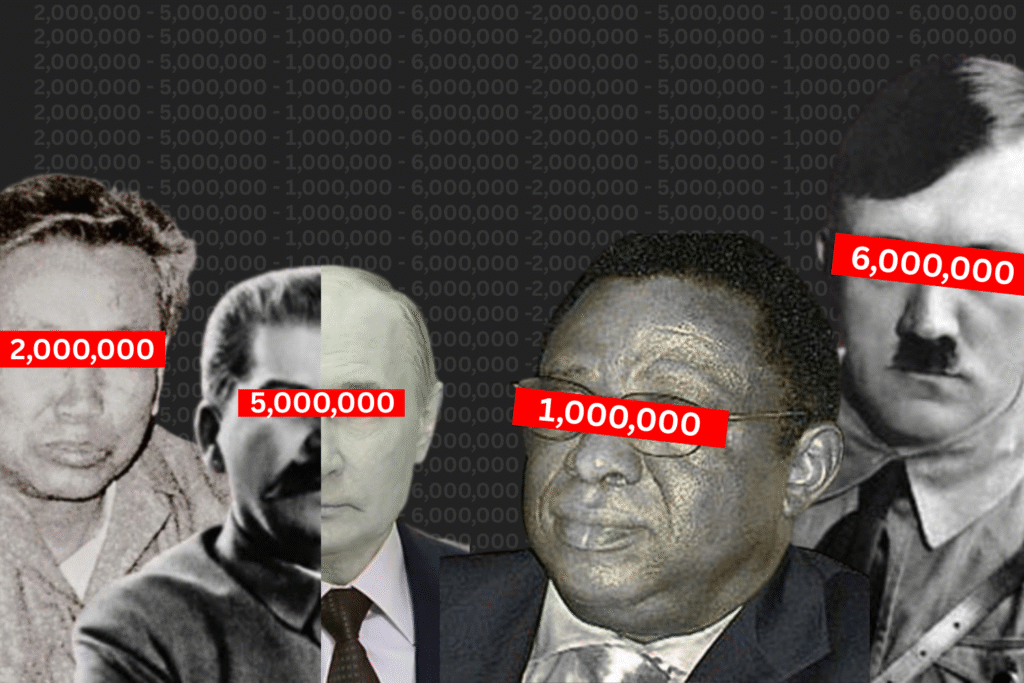

In April 1994, extremist leaders within the Hutu-led government launched a coordinated plan to eliminate the Tutsi minority. Over around 100 days, about 800,000 Tutsi civilians and moderate Hutus were murdered by government forces, militias, and ordinary citizens.

Legal Issues

The world had advance warnings. Under the Genocide Convention, states had a legal obligation to act, yet intervention never came.

After the genocide, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda prosecuted top officials. These trials created important legal precedents, especially on incitement through media and command responsibility.

However, they occurred only after the destruction was complete, showing how prevention mechanisms were legally inadequate. Also, the backlogs for the trials were so large, that cases were sometimes diverted to local level courts, (gacaca) allowing genuine war criminals to get off easily.

Ukraine

Background

Ukraine has experienced two major atrocities relevant to genocide law.

- The Holodomor famine of 1932 to 1933 caused millions of deaths and is widely seen as a genocide.

- Since 2022, Russia’s invasion has produced allegations of mass killings, forced deportations, and attacks on civilian infrastructures, with Putin even officially having a warrant out for his arrest

These two events are slightly short of a hundred years apart and took place under two seemingly very different regime. Yet, both were and are examples of the cruel capabilities of our fellow humans.

Legal Issues

The current war has prompted investigations by the International Criminal Court into forced transfers of children and civilian targeting. But Russia is not a party to the ICC, which limits jurisdiction. This demonstrates a structural weakness in the international legal system.

The Holocaust

Background

Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany systematically murdered six million Jewish people along with millions of Roma, disabled people, LGBTQ+ individuals, Slavic peoples, and political opponents. The killings took place through ghettos, mass shootings, forced labour, and extermination camps. It is something that we should never forget – and if we do, well, at least we will know one thing: We have reached a new low.

Legal Issues

The Holocaust directly shaped modern international criminal law:

- It led to the Nuremberg Trials

- It inspired the Genocide Convention

- It influenced the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

- It led to the systematic hunting of war criminals by organisations across the world

And yet, despite the enormity of this tragedy, it would be incorrect to say that it produced a perfect international criminal law system. If there wasn’t enough tragedy already, it seems we left ourselves room to commit more unspeakable acts.

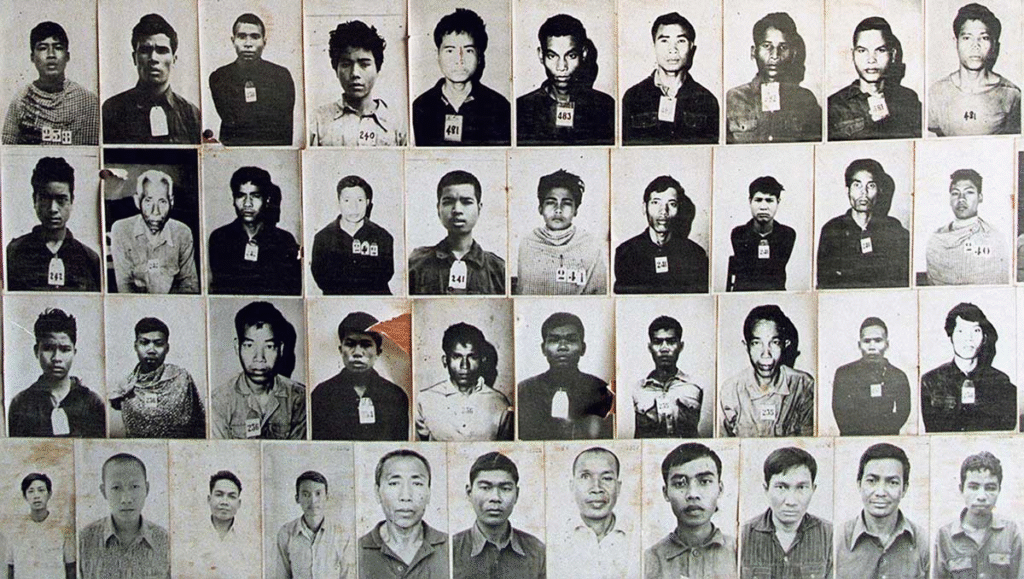

Cambodia

Background

The Khmer Rouge regime led by Pol Pot attempted to create a radical agrarian society. Intellectuals, minorities, urban dwellers, and perceived political opponents were targeted. Nearly two million people were killed through execution, forced labour, starvation, and disease.

Legal Issues

Despite widespread knowledge of atrocities, no international intervention occurred. Decades later, the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia prosecuted several senior leaders.

The long delay and limited number of convictions reveal a legal system unable to respond quickly during periods of state collapse and international indifference.

And unfortunately, so on…

The list does not end here. Gaza. Bosnia. Srebrenica. Darfur. Myanmar. The Yazidi people under ISIS. And many more. Each new atrocity proves that the promise of “never again” has become more of a hope than a legal reality. The Genocide Convention imposes a duty to prevent and punish, yet time after time, the world has responded with hesitation, political double standards, and delayed justice. International courts open cases only after mass graves are discovered. Investigations begin only once communities have been destroyed. Legal rulings arrive long after survivors have lost family, homes, and futures.

These repeated failures reveal an uncomfortable truth. The international legal system was built to stop genocide, but too often it merely documents it. Until law becomes more than words and more than retrospective judgment, the cycle will continue. And tragically, the world will add yet another name to this growing list.